The Earth's Internal Structure

- Geologist M.Mahfouz

- Dec 23, 2017

- 9 min read

The Earth's Internal Structure

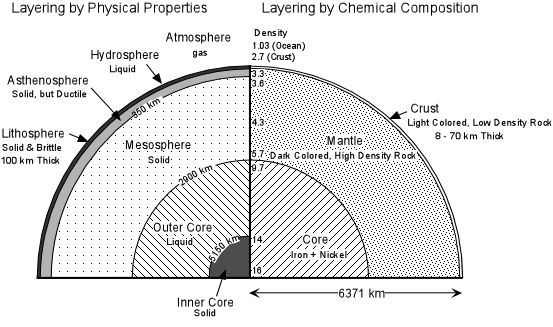

Evidence from seismology tells us that the Earth has a layered structure. Seismic waves generated by earthquakes travel through the Earth with velocities that depend on the type of wave and the physical properties of the material through which the waves travel.

A- Layers of Differing Chemical Composition

Crust - variable thickness and composition

Continental crust (SiAl) 10-70 km thick, underlies all continental areas, has an average composition that is granitic.

Oceanic crust (Sima) 8-10 km thick, underlies all ocean basins, has an average composition that is basaltic.

- has a thickness of 2800 kilometers, made up of ultramafic rock called peridotite.

- 3500 kilometers in radius, made up of Iron (Fe) and small amount of Nickel (Ni), the composition of iron meteorites.

B-Layers of Differing Physical Properties

Lithosphere - about 100 km thick, very brittle, easily fractured at low temperature. Note that the lithosphere is comprised of both crust and part of the upper mantle. The plates that we talk about in plate tectonics are made up of the lithosphere, and appear to float on the underlying asthenosphere.

Asthenosphere - about 250 km thick - solid rock, but soft and flows easily (ductile). The top of the asthenosphere is called the Low Velocity Zone (LVZ) because the velocities of both P- and S-waves are lower than the in the lithosphere above. But, not that neither P- nor S-wave velocities go to zero, so the LVZ is not completely liquid.

Mesosphere - about 2550 km thick, solid rocks rich in Si, O, Fe, Mg, but still capable of flowing.

Outer Core - 2200 km thick - liquid. We know this because S-wave velocities are zero in the outer core. If Vs = 0, this implies m = 0, and this implies that the material is in a liquid state.

Inner core - 1228 km radius, solid

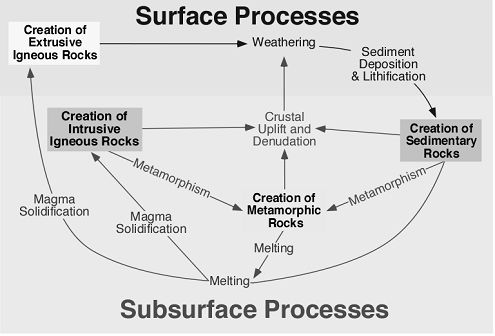

A rock can be defined as a solid substance that occurs naturally because of the effects of three basic geological processes: magma solidification; sedimentation of weathered rock debris; and metamorphism. As a result of these processes, three main types of rock occur:

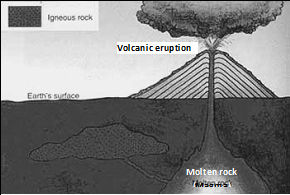

Igneous Rocks- produced by solidification of molten magma from the mantle. Magma that solidifies at the Earth's surface conceives extrusive or volcanic igneous rocks. When magma cools and solidifies beneath the surface of the Earth intrusive or plutonic igneous rocks are formed.

Sedimentary Rocks- formed by burial, compression, and chemical modification of deposited weathered rock debris or sediments at the Earth's surface.

Metamorphic Rocks- created when existing rock is chemically or physically modified by intense heat or pressure.

The rock cycle

The rock cycle is a general model that describes how various geological processes create, modify, and influence rocks. This model suggests that the origin of all rocks can be ultimately traced back to the solidification of molten magma. Magma consists of a partially melted mixture of elements and compounds commonly found in rocks. Magma exists just beneath the solid crust of the Earth in an interior zone known as the mantle.

Igneous rocks form from the cooling and crystallization of magma as it migrates closer to the Earth's surface. If the crystallization process occurs at the Earth's surface, the rocks created are called extrusive igneous rocks. Intrusive igneous rocks are rocks that form within the Earth's solid lithosphere. Intrusive igneous rocks can be brought to the surface of the Earth by denudation and by a variety of tectonic processes.

All rock types can be physically and chemically decomposed by a variety of surface processes collectively known as weathering. The debris that is created by weathering is often transported through the landscape by erosional processes via streams, glaciers, wind, and gravity. When this debris is deposited as a permanent sediment, the processes of burial, compression, and chemical alteration can modify these materials over long periods of time to produce sedimentary rocks.

A number of geologic processes, like tectonic folding and faulting, can exert heat and pressure on both igneous and sedimentary rocks causing them to be altered physically or chemically. Rocks modified in this way are termed metamorphic rocks.

All of the rock types described above can be returned to the Earth's interior by tectonic forces at areas known as subduction zones. Once in the Earth's interior, extreme pressures and temperatures melt the rock back into magma to begin the rock cycle again.

Magma

As described above, the igneous rocks are produced by the crystallization and solidification of molten magma. Magma is the term used to describe molten material within the Earth; in simple terms: molten rock. But the molten rock usually contains some suspended crystals and dissolved gases, i.e. magma is a mixture of liquid rock, gases, and mineral crystals. The main elements in magma are oxygen (O), silicon (Si), aluminum (Al), calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), potassium (K), iron (Fe), and magnesium (Mg). However, it is two major molecules found in magma that controls the properties of the magma. These two molecules are silica (SiO2) and water (H2O). Silica comprises as much as 75 percent of the magma.

Magma can cool to form an igneous rock either on the surface of the Earth - in which case it produces a volcanic or extrusive igneous rock, or beneath the surface of the Earth - in which case it produces a plutonic or intrusive igneous rock.

The type of igneous rocks that form from magma is a function of three factors: the chemical composition of the magma; temperature of solidification; and the rate of cooling which influences the crystallization process.

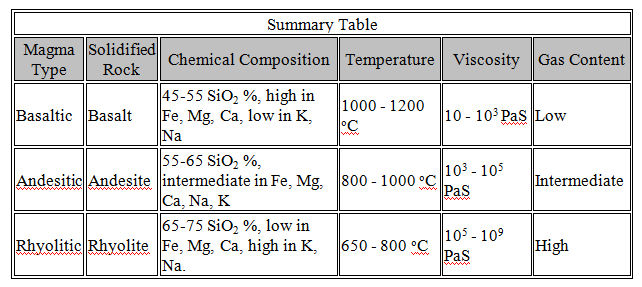

Types of magma are determined by chemical composition of the magma. Three general types are recognized, but we will look at other types later in the course:

magma -- SiO2 45-55 wt%, high in Fe, Mg, Ca, low in K, Na

magma -- SiO2 55-65 wt%, intermediate. in Fe, Mg, Ca, Na, K

magma -- SiO2 65-75%, low in Fe, Mg, Ca, high in K, Na

Gases in Magmas: At depth in the Earth nearly all magmas contain gas dissolved in the liquid, but the gas forms a separate vapor phase when pressure is decreased as magma rises toward the surface. This is similar to carbonated beverages which are bottled at high pressure. The high pressure keeps the gas in solution in the liquid, but when pressure is decreased, like when you open the can or bottle, the gas comes out of solution and forms a separate gas phase that you see as bubbles. Gas gives magmas their explosive character, because volume of gas expands as pressure is reduced. The composition of the gases in magma are:

Mostly H2O (water vapor) with some CO2 (carbon dioxide)

Minor amounts of Sulfur, Chlorine, and Fluorine gases

The amount of gas in a magma is also related to the chemical composition of the magma. Rhyolitic magmas usually have higher dissolved gas contents than basaltic magmas.

Temperature of magmas is difficult to measure (due to the danger involved), but laboratory measurement and limited field observation indicate that the eruption temperature of various magmas is as follows:

Basaltic magma - 1000 to 1200oC

Andesitic magma - 800 to 1000oC

Rhyolitic magma - 650 to 800oC.

Viscosity of Magma is the resistance to flow (opposite of fluidity). Viscosity depends on primarily on the composition of the magma, and temperature.

Higher SiO2 (silica) content magmas have higher viscosity than lower SiO2 content magmas (viscosity increases with increasing SiO2 concentration in the magma).

Lower temperature magmas have higher viscosity than higher temperature magmas (viscosity decreases with increasing temperature of the magma).

Thus, basaltic magmas tend to be fairly fluid (low viscosity), but their viscosity is still 10,000 to 100,0000 times more viscous than water. Rhyolitic magmas tend to have even higher viscosity, ranging between 1 million and 100 million times more viscous than water. (Note that solids, even though they appear solid have a viscosity, but it is very high, measured as trillions time the viscosity of water). Viscosity is an important property in determining the eruptive behavior of magmas.

Magma cools below the Earth's surface, but Lava erupts onto the Earth's surface through a volcano or crack (fissure). Lava cools more quickly because it is on the surface. Cooling rates influence the texture of the igneous rock:

Quick cooling = fine grains

Slow cooling = coarse grains

In general, the slower the cooling, the larger the crystals in the final rock. Because of this, we assume that coarse grained igneous rocks are "intrusive," in that they cooled at depth in the crust where they were insulated by layers of rock and sediment. Fine grained rocks are called "extrusive" and are generally produced through volcanic eruptions.

Grain size can vary greatly, from extremely coarse grained rocks with crystals the size of your fist, down to glassy material which cooled so quickly that there are no mineral grains at all. Coarse grain varieties (with mineral grains large enough to see without a magnifying glass) are called phaneritic. Granite and gabbro are examples of phaneritic igneous rocks. Fine grained rocks, where the individual grains are too small to see, are called aphanitic. Basalt is an example. The most common glassy rock is obsidian. Obviously, there are innumerable intermediate stages to confuse the issue.

We broadly categorize igneous rocks by: 1) genesis, 2) composition, and 3) texture. Their genesis refers to the environment where the igneous rock formed, which is strongly influenced by depth below the surface. These three categories are called "plutonic, volcanic and hypabysal".

Genetic Classification of Igneous Rocks

Plutonic (Intrusive):

Crystalline rocks formed by crystallization of magma at great depth below the surface, resulting in slower cooling and/or greater fluid content

Coarse-grained sizes (greater than a millimeter); equigranular to porphyritic

Volcanic (Extrusive):

Crystalline rocks formed by crystallization of magma at the surface, which rapidly crystallizes (quenches) as it comes into contact with the atmosphere or within a body of water.

Fine-grained textures (less than a millimeter); equigranular to porphyritic to porphyry textures.

Hypabyssal:

Crystalline rocks formed by crystallization of magma at a shallow depth below the surface

Mixed fine- to medium-grained textures; equigranular to porphyritic to porphyry textures

Plutonic means deep underground (plutonic). Another name for plutonic rocks is “intrusive”, because they intrude or invade other rocks. Volcanic means extruded at the surface. Another name for these rocks is “extrusive”, because they are extruded onto the surface. They may be extruded into the air or underwater, which are called “subaerial” and “submarine” environments, respectively. Hypabysal means intruded into rocks at near surface conditions. Hypabysal rocks often occur in the form of smaller types of intrusions, like dikes, sills or plugs. Hypabysal rocks are often found in close association with volcanic rocks because they often form the feeder systems for volcanic lava being extruded at the surface.

Compositions of Igneous Rocks

The compositions of igneous rocks can be broadly subdivided into four major types. These are felsic, mafic, intermediate and ultramafic.

Felsic: “Fel” from feldspar, and “sic” from silicon; generally light colored. A rock made up of abundant silica, aluminum and alkalis (potassium, sodium, calcium) due to the presence of abundant feldspar and quartz.

Mafic: “Ma” from magnesium and “fic” for iron; generally dark colored. A rock with abundant magnesium and iron, due to the presence of abundant iron-magnesium-bearing minerals (such amphibole or pyroxene).

Intermediate: Contains a balance between the minerals quartz plus feldspar, and mafic minerals; generally moderate in tone and color.

Ultramafic: Composed chiefly of the iron-magnesium minerals pyroxene and olivine.

The most common igneous rock types are categorized below on the basis of color and genesis:

Bowen’s Reaction Series

Bowen’s Reaction Series is a theory concerning the crystallization process which occurs when a magma cools. As a magma cools, individual mineral species selectively crystallize at some unique temperature. Thus we have some minerals crystallizing very early in the cooling history when the melt is still extremely hot, and other minerals which crystallize at successively lower and lower temperatures. The reaction series has two branches, shown below:

A “discontinuous reaction series” is where the early formed minerals react with the melt to form completely new mineral species. An example of a discontinuous reaction series is the reaction of the very high temperature mineral olivine with the melt to form pyroxene. With further cooling, pyroxene reacts with the remaining melt to form amphibole. Amphibole reacts with the melt to form biotite. Each new mineral forms at a lower and lower temperature. This sequence is shown graphically on the left side of the diagram.

In a “continuous reaction series” the crystals react with the melt but do not form completely new mineral species. Instead, ionic diffusion causes an exchange or ions to occur in the crystal lattice of the mineral, resulting in a ‘modified’ composition. The primary example of continuous reaction is that of Ca-rich plagioclase (or anorthite). The continuous reaction of anorthite with the melt causes the anorthite to change its composition to become a more Na-rich plagioclase (or albite). This sequence is shown graphically on the right side of the diagram.

That the composition of melt changes, and that crystals change their composition over time is evidenced by the observation of rims of albitic plagioclase on anorthitic plagioclase in some plutonic rocks. Furthermore, it is also known that anorthite is the most common plagioclase in basaltic (or mafic) igneous rocks, and albite is the most common plagioclase in rhyolitic (or felsic) igneous rocks. Thus, mafic igneous rocks have higher melting temperatures, because they are comprised mostly of high temperature minerals. Felsic igneous rocks have lower melting temperatures, because they are comprised mostly of low temperature, and even hydrous minerals. At one time it was believed that the evolution of a basaltic magma, by continuous modification of its melt composition by fractional crystallization, could result in the formation of a residual magma of rhyolitic composition. Currently, this type of extreme differentiation is thought to be very rare, although it is widely accepted that fractional crystallization plays an important role in creating a wide variety of igneous rock compositions from the same parent magma.

Comments